Society is an extremely complex system. People interact in an intricate network of relationships, both on a personal level or as part of more complex institutions (companies, associations, political parties, religions, geographical communities). This makes it very difficult to analyze − and therefore, to predict − how the system will evolve over time. Will those interactions bring to an improvement of conditions for most people? Nobody can say for sure, and the road to progress is a bumpy one.

But there are certainly ways to look at this complexity and still make some educated guesses on what can (and likely will) happen. One such way is to look at where are the incentives in the system. People (and any other entities in the system) are likely to do what brings them a benefit. While benefit itself is a very wide concept that can mean different things for different people, a very common type of benefit is definitely at the center of how our civilization operates: financial gains. People (and even more so companies) are likely to do what brings them a financial benefit.

Admittedly, this is a simplification, as people are also driven by other incentives. There are benefactors that are willing sacrifice some wealth for the benefit of other people. There are magnates that are willing to finance enterprises (or even artists) for some greater good, because they want to bring an improvement to the world.

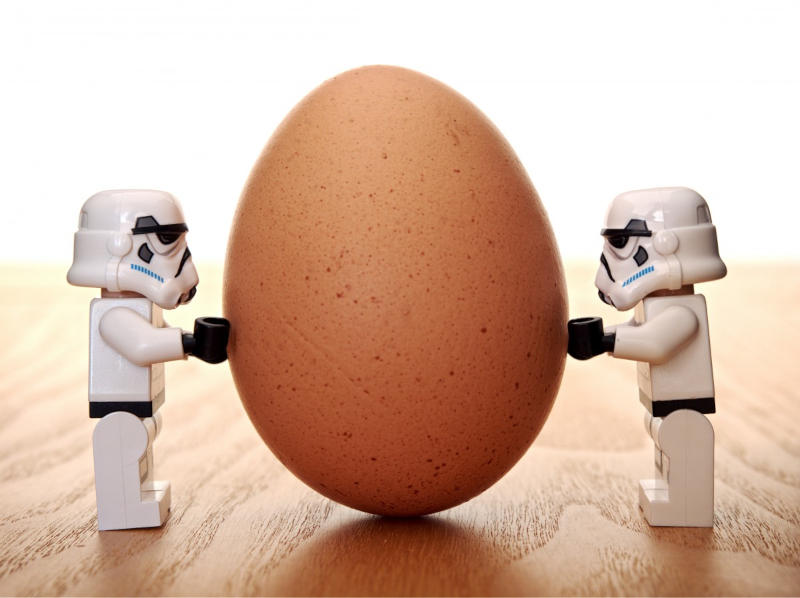

Yet, making sure that the financial incentives of the participants in a system are aligned with the goals and values of the system is of paramount importance. When that happens, the natural state of the system is such that the satisfaction of certain properties is guaranteed, and a small deviation will naturally be met with an opposite force that brings the system back to its equilibrium. Instead, a system where the incentives are not aligned is like the egg in the picture above, that needs an external force to stay in place. When that force is removed, the egg will roll on its side, and if you’re unlucky, you’ll soon find it splattered on the ground.

Discovering that the incentives of participants of a system are not aligned with the desired properties and behavior of the system itself is a red flag that calls into question its long term sustainability.

In this article, we explore the incentives at play in the process of printing money, for different forms of money − and why Bitcoin is different.

Governance and money production

Who prints the money? In early forms of money, the answer was nobody: money likely emerged without any central authority. People naturally appreciated certain items, which made them desirable to collect, which in turn led to the appearance of the monetary properties of those items out of pure necessity. [1] By virtue of being the right combination of rare and hard to make, shells, wearables and jewelry naturally served the purpose of facilitating trade.

Among the collectibles, precious metals like silver and gold eventually took over as better forms of money, as they had many desirable properties for a monetary medium: they are easy to carry and to protect, they are relatively easy to assess in terms of quality to decide their value, and they are rare in nature. Scarcity is essential: valuable items bring a constant incentive to find or produce more of them, therefore flooding the market (and crashing the price) of anything that is not hard to find/produce.

Coinage

The invention of coinage made them much easier to use for day-to-day trade: by forging metals in standardized forms, with coins that always contained the same amount of the precious metal, one could easily use them as units of value, making it possible to pay someone else any exact amount by choosing the right amount of the right coins. As coins were issued by someone as trusted as the King, the convenience was greatly increaed as well, as people didn’t have to check how much precious metal was in each coin (assuming that there are not too many fake coins in circulation).

With coinage comes debasement

Unlike raw metals, coins are designed to always have the same value. Therefore, they have a serious defect: by removing small amounts of the material used to make the coin, you extract some precious metal without changing the face value of the coin itself. Multiple methods of coin debasement existed to shave off some of the juicy metal − which were, of course, illegal.

Governments weren’t immune to the temptation to do the same − with the additional benefit that nobody could jail them for it. The Roman Denarius, which had 6.81g of silver in 267 BC, was progressively retariffed with smaller amounts of precious metals in later coinages, by decreasing both its weight and its purity. By 241 AD it weighed 3.31g, half the original weight, with its purity reduced to just 48% by making alloys with other cheap metals.

Incentive analysis

- People have the incentive to debase coins by shaving them.

- Government have the incentive to debase the currency, either by shaving them or by a new coinage with a smaller amount of precious metal.

Representative money

As a way to overcome the shortcomings of commodity money (where the value of the coin equals the value of the commodity making it), representative money was used instead: here, the coins (or paper notes) have carry little or no value, but they represent a claim on some commodity that is stored and guaranteed in a safe place.

Commodity-backed money was widely used in modern times, backed by silver or by gold. The convertibility with the commodity that the claim represents ensured that, to all practical effects, the coins and notes could be used in place of the backing commodity. Except in one aspect, that is not strictly practical, therefore goes unnoticed in the short term: it alters the incentives.

Incentive analysis

- Shaving coins is pointless. People have an incentive to debase the currency by making counterfeit coins that look just like the real ones. As long as a proper effort is put into place to make it difficult (or risky by means of hefty punishments), this can become unlikely.

- The central authorities has a clear incentive to debase the currency by covertly creating coins or notes in excess to the ones that are backed by the actual reserves, or to unilaterally change the conversion rate against the backed asset.

- In the most extreme case, the government can exploit the dominant position of the currency to end the convertibility against the backed asset, as the 1971 Nixon shock.

In some instances (including the Nixon shock) such measures were called “temporary”. But while there is an incentive to introduce them, there is no incentive in reversing them!

Fiat money

Once the backing is removed completely, we reach the most modern form of centralized money: fiat money, which is money by decree. It doesn’t have any intrinsic value, nor it is backed by anything that has value and is stored elsewhere.

The government cannot directly print money. Central banks, instead, can expand the money supply by extending loans.

Governments can sell government bonds in order to get extra money to spend, therefore getting indebted. But when these bonds end up into the balance sheet of central banks, that results in an increase of money supply (=money printing).

Incentives analysis

- Public debt: there is a clear, perpetual incentive for the current politicians to increase public debt. That gives them money to spend now, while any negative consequences will be suffered by someone else in the future¹.

- Money supply expansion: banks make money out of loans they extend, and the state is usually a trusted client. So when government emit bonds, a large fraction tends to be purschased from central banks.

Given that governments have an incentive to increase debt, and banks have a financial incentive to purchase government debt, one would expect that, over time:

- politicians will use their power to influence banks so that they can increase the amount of public indebtedness

- central banks will increase the amount of government bonds in their balance sheets, in turn becoming less independent from the government.

What’s going to happen?

By looking at the incentives of each of the money systems above, we can summarize as follows:

- Early forms of money were replaced by precious metals

- Convenience leads to precious metals being adopted by means of coinage

- Incentives lead to commodity money being replaced by representative money (backed by reserves)

- Incentives lead to representative money overgrowing its reserves, and eventually to become fiat money

And what will happen to fiat money? The incentives simply suggest that governments will keep getting indebted, and central banks will keep buying this debt, therefore increasing the money supply. As the economic rubberband keeps getting stretched, I see only two possible outcomes:

- Government default. The government admits that the debt is never going to be paid back.

- Money is printed directly to pay off debt, with a direct, huge increase of the monetary base which will devaluate the currency heavily.

Both will have large scale consequences that are hard to predict, and frankly quite scary.

But what do I know? I’m not an economist. Years ago, I was discussing the second option with a friend who know much more than me about the inner workings of macroeconomics, and he told me that the second option is an absurdity. Except that it is now a regular topic of discussion in the US political debate, see for example here.

Bitcoin and incentives

Like any distributed protocol, making sure that incentives were aligned was certainly one of the aspects that kept Satoshi awake. As Bitcoin still didn’t collapse, it looks like they did a good job.

There are many participants in the system, with different sets of incentives; a full discussion can’t prescind from a detailed technical discussion of how Bitcoin works, and it goes beyond the scope of this post. Here, I just want to discuss the incentives at play in the process of minting new Bitcoins. In other words, who prints new coins? What prevents them from printing more?

Nodes and rules

The Bitcoin network is composed of (at least) tens of thousands of nodes. Each of them is a machine that is connected to the Internet, and it does a bunch of things that keep the network alive. The most important task is that of verifying a certain number of consensus rules: each node will refuse to propagate a transaction or a block that violates the rules. A special kind of node software is used by miners: they are the only ones that can actually add a new block to the blockchain; a new block is where the new transactions are stored, so there is no progress without miners. Running a miner requires specialized hardware that is built to participate in Proof of Work mechanisms that secures the blockchain.

New Bitcoins are issued for every new block, according to a scheduled that Satoshi set in stone since the beginning: initially, the miner that created a block were rewarded 50 ₿. But the reward is halved about every 4 years (more precisely, every 210000 blocks). Therefore, in November, 2012, the reward became 25 ₿, then 12.5 ₿ in July 2016, and only 6.25 ₿ in May 2020. Sometime aroung year 2140, the issuance of new bitcoins will stop completely, and the network will only circulate the existing coins.

Changing the rules

Because the network is designed to kick out any bad guy that does not respect the consensus rules, no participant of the network has the incentive to violate them. Therefore, a node that tried to publish an invalid transaction (or a miner who tried to propagate an invalid block assigning 1000 ₿ to himself) would be very disappointed.

But after all, rules are part of the software, and the software can be changed. What prevents the majority of the nodes to change the rules, and − say − bring the block reward to 1000 ₿? You name it: incentives! Why would they? Most of the nodes that participate to the economic activity (buying, selling or holding bitcoins) own some of them. Therefore, implementing new rules that decrease the value of the coins they possess goes against their financial incentive.

The only rule changes that can find consensus of the majority of the nodes are those that improve Bitcoin for everyone, or at least the vast majority of the users².

It is a sometimes claimed that the majority of the miners can change the rules if they want to do it. That would be a problem, as they clearly have a potential interest in doing so, for example by issuing more coins so they can earn more money. A detailed discussion of whether this is possible is out of scope for this post. The short answer is: they could potentially impose some types of changes that can be implemented via a soft-fork (for example: censoring some transactions); but changing the issuance requires a hard-fork. The fact that even a supermajority of miners can’t easily impose a hard-fork was tested in 2017 when miners abandoned the contentious Segwit2X hard-fork proposal that was supported by a majority of 90% of the miners, once it became clear that the market supported the regular Segwit soft-fork instead.

Therefore, we can be reasonably certain that Bitcoin won’t ever introduce inflation, because it’s incentive-aligned with its absence.

What does this mean?

This paragraph is about the future, therefore it’s purely my opinion. There’s plenty of people who thinks that Bitcoin will fail and go to zero, or that it’s probably rat poison squared (but at least, by virtue of being squared, it should never go below zero, unlike oil!). Do your own research and invest in learning first and foremost.

At the time of writing, the price of 1 ₿ is above 11000$, and the total value of all Bitcoins in circulation is just above 200 billion dollars, which is still a relatively small number in the scale of global economy (see [2] for a great comparative visualization of the size of different type of money and other assets).

Therefore, it’s still too small to have a substantial impact on the world economy. But it now exists. While it is still not widely considered as a savings technology, recognition is growing. Hedge fund manager Paul Tudor Jones bought Bitcoin; using his words, “Every day that goes by that Bitcoin survives, the trust in it will go up”. More recently, The Business Intelligence company MicroStrategy bought 250M $ worth of Bitcoin, allocating to it 20% of their cash reserves.

As Bitcoin has a number of properties that make it a better saving technology than anything else that exists, I expect Bitcoin to still grow in terms of market capitalization; more people, companies and funds will start using it as hedge against economic collapse, rather than a speculation; this will help stabilize its value. Less volatility will lead to even more people and companies allocating it as part of their savings.

How much of the world’s wealth will ultimately be stored in Bitcoin is anyone’s guess. But if it doesn’t fail, people will have a real savings technology that is free and permissionless, cannot be debased or controlled by any central party.

This will have profound implications, which I can’t claim to fully understand. But I believe that saving is common sense, and that’s what Bitcoin brings back.

Bitcoin restores the right to save.

References

- Nick Szabo, Shelling Out: The Origins of Money

- Jeff Desjardins, All of the World’s Money and Markets in One Visualization

Footnotes

¹ Unless you believe that you can have the free cake since “debt is money that we owe to ourselves” like a famous economist, an argument that would make anyone extremely wary, unless they studied economics.

² Well, even in that case, it’s a long and difficult process that typically requires years. The 2017 Segregated Witness upgrade was in the works since 2015.